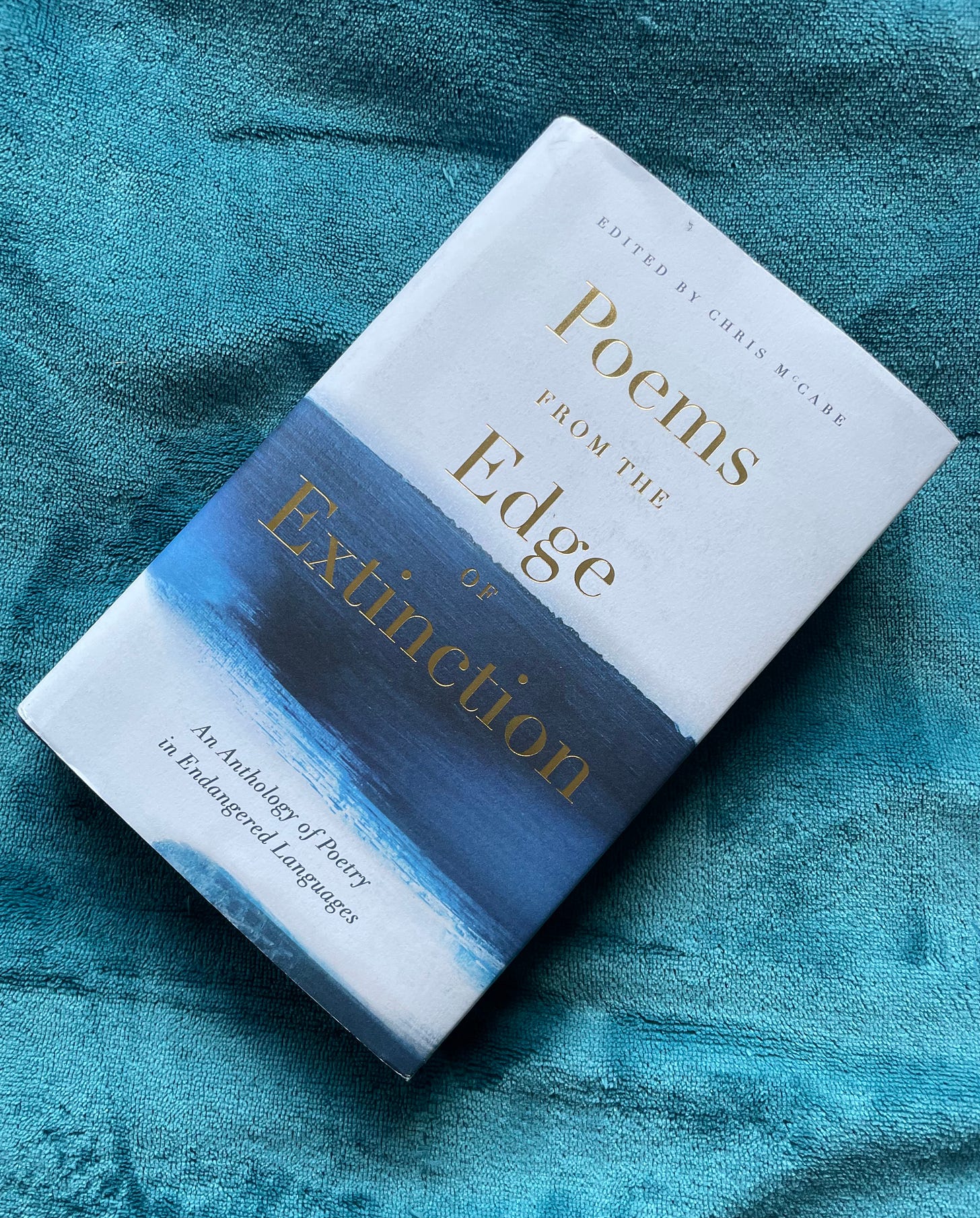

Poems from the Edge of Extinction

On the beauty and importance of the diversification of language.

Welcome to The Autumn Chronicles, a place to shine a light on all the wonder around us as we navigate the seasons. I hope these writings allow you to sit quietly with a cup of something warm and comforting and take a few moments for yourself away from the rush and hurry. If you would like to make sure you get all newsletters directly to your inbox, please subscribe below. Thank you for being here. All photos © The Autumn Chronicles.

Almost 20 years ago, I went on holiday to California with a friend. I was in a hotel lobby in Los Angeles, not long off a transatlantic flight, enquiring about guided tours of the city (it’s not an easy one to navigate for pedestrians or via public transport), when I overheard one of the receptionists talking in Spanish with one of the porters. I had never seen or spoken to them before that day but, judging by their conversation, they had taken an immediate dislike to my clothes, to my hair, to my figure. I waited for them to finish their conversation and then reminded them, politely and also in Spanish, that you can never assume someone does not understand the language you are speaking. They at least had the good grace to look contrite and I finally felt like I had put that Hispanic Studies degree to good use.

According to Chambers, the publisher of the gorgeous book ‘Poems from the Edge of Extinction: An Anthology of Poetry in Endangered Languages’, edited by Chris McCabe:

One language is falling silent every two weeks. Half of the 7,000 languages spoken in the world today will be lost by the end of this century.

When a language is extinguished, we lose more than just words. We lose access to cultural traditions and histories, to unique constructs of grammar and cadence that enable us to understand ways of life that differ from our own. In these times of globalisation, there is an argument to say that languages are becoming more homogenous. English has long been the dominant language of industry and commerce, being spoken by roughly 17% of the global population, and friends of mine who are native speakers of other languages have shared with me many examples where a word has been absorbed into their mother tongue in English, rather than via translation (bonjour, le weekend). While the streamlining of languages can make connection easier in a global world, encouraging closer links and better understanding between peoples and nations, when there is also the potential for endangerment of language - and therefore of established customs and cultures - it then becomes vital to retain access to them to preserve our comprehension of those ways of life.

It is for this reason that this book is so important. It is an anthology of 50 poems, written in languages that have been marked as at risk for extinction. Some of the poems are written by poets who are the last speakers of languages that have traditionally been passed down orally, so recording them in written form becomes ever more important to ensure they are not lost completely to the mists of time. Diversification of language is fundamental, both for the story of humanity to which it contributes but also because of the lessons - and inspiration - that can be drawn today from historical linguistic traditions.

Each poem is included in the book in its native form and as an English translation, with an additional short essay providing information about the author and the language under discussion. There are poems in languages from Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Oceania so the breadth is vast. One of my favourites is a poem called Lágri Di Amor (Tears of Love) by Miguel de Senna Fernandes, originally written in a language called Patuá. Patuá is a Creole language spoken by the Macau people in the Pearl River Delta, near to Hong Kong. It is a diverse fusion of Portuguese, Malay, Konkani and Spanish, with influences from Hindi, Japanese and Cantonese as a result of the trade routes its speakers travelled over the centuries. Another poem that I loved is called Duillagyn Ny Fouyir (The Leaves of Autumn), written in Manx by Robert Corteen Carswell. Manx is the language traditionally spoken on the Isle of Man, a small island in the Irish Sea. Manx is closely linked to Irish Gaelic and potentially has some influences from Scandinavian languages. The earliest records of written Manx show the language taking a runic form, meaning it was likely brought to the island, or at the very least influenced, by Viking raiders.

Poems from the Edge of Extinction is a fascinating read for language students, anyone curious about the world around us and for people who are drawn to understanding the way language has shaped where we have come from and where we are going.

If you have enjoyed this post or if something has resonated with you, please share to help others find The Autumn Chronicles. I am so grateful to you for being here and for choosing to read these words.

A brilliant read - shame on those idiots, hopefully they learned to keep their manners better. Insightful on the use of languages and also the communities that use them. Might peruse the bookshelf for a copy of the poems.x

I'm really sorry to read about your experience with such disgusting people, I LOVE that you told them straight in their language though! Brilliant! I am fascinated by languages. I have a side-job with a cruise company and I'm always in awe of how many languages people from around the world seem to speak. I almost feel ignorant for not being able to speak another language fluently but I always make the effort to learn the basics for anywhere I visit, I feel it goes a long way with the locals.